As part of the "Here Come the Girls" project by the Royal Greenwich Heritage Trust, Lynne has been researching the Well Hall Estate, in particular the families and daily lives of those who moved into the Estate from 1915.

Garden City for Arsenal Workers:

The Well Hall Estate

|

| Postcard c 1915 Royal Greenwich Heritage Trust |

This is some background to the design and building of the Progress Estate, Well Hall, during the period of the First World War when it was known as the Well Hall Estate. It is not going to be a comprehensive history of the first few years of the estate’s existence – that is covered in other places. For those who would like to have further background history, there’s the entry on the Ideal-homes website about the estate www.ideal-homes.org.uk/case-studies/progress-estate. Alternatively local historian Keith Billinghurst is writing a book which will be published later in the year, more details on this will be published on Progress Estate website here.

A housing shortage

No doubt sooner or later the agricultural land at Well Hall would have been submerged beneath housing in the period between the two world wars when London’s suburbs grew and grew. The First World War speeded up that process for 90 acres of the land and helped create about 1300 distinctive, publicly owned houses in the form of an attractive and highly regarded estate. The Well Hall Estate, Eltham, which was also called the Well Hall Garden Suburb or City, was not so much ‘homes fit for heroes’ – those came later – as homes fit for workers, workers at the Royal Arsenal, Woolwich. We owe its presence, ironically, to the generally destructive First World War which led to the huge expansion of production at the Arsenal during the first months of the war in 1914. By the end of the year Woolwich Borough Council was petitioning the Local Government Board a central government organisation, for housing for the vast numbers of workers newly arrived or about to arrive in the area. In January 1915 the council highlighted the need for housing for the working classes.

Employment at the Arsenal had risen from 13,266 in August 1914 to 28,000 by the end of the year and was expected to rise another 7,000 in the next three months. There was reported to be no vacant accommodation in Woolwich suitable for persons of the working class. The shortage of housing in Woolwich had also been exacerbated by the pressure for married quarters for army families. As it was, thousands of workers travelled to the Arsenal from both north and south of the river. This need for housing was supported by the War Office. Once a decision was made to build the houses by the Office of Works, things moved incredibly swiftly. The Office of Works’ principal architect, Frank Baines, and colleagues visited the chosen site of 90 acres of agricultural land and within days a plan had been drawn up. The land chosen was used for market gardening on either side of Well Hall Road which a decade or so before had been Woolwich Lane. Astonishingly, within twelve months the estate was completed.

The design

The estate owes its character to its principal architect, Frank Baines, later Sir Frank Baines, who also designed the MI5 building on the Thames as well as many other housing estates, including one at Roe Green for workers in the nearby aircraft factory.

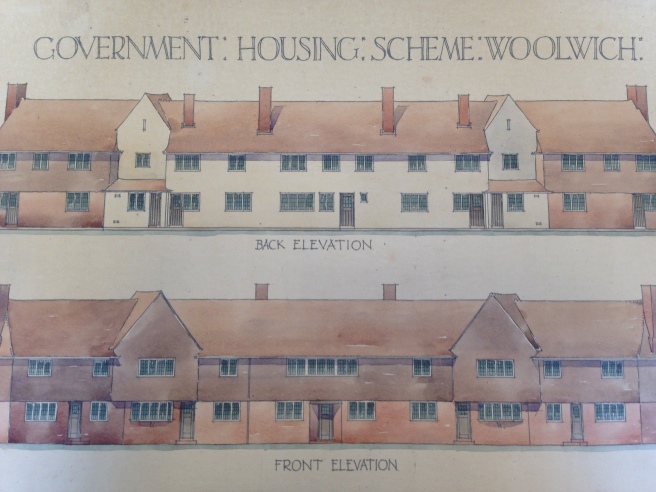

|

| c 1915 Royal Greenwich Heritage Trust |

Work on building began on 8th February just a few weeks after the decision to build had been taken and the first houses were completed on May 22nd and occupied not long after. The whole estate was completed by December with a reported 3,700 names on the waiting list.

No comments:

Post a Comment